BT Tower

| BT Tower | |

|---|---|

BT Tower in 2022 | |

| |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the United Kingdom from 1964 to 1980[I] | |

| Preceded by | Millbank Tower |

| Surpassed by | Tower 42 |

| General information | |

| Type | Offices[1] |

| Location | London, W1T United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°31′17″N 0°08′20″W / 51.5215°N 0.1389°W |

| Construction started | 1961 |

| Completed | 1964[1] |

| Owner | British Telecommunications plc |

| Height | |

| Antenna spire | 620 feet (189 m)[2] |

| Roof | 581 feet (177 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 37 |

| Lifts/elevators | 2 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Eric Bedford |

| Main contractor | Peter Lind & Company |

The BT Tower is a grade II listed communications tower in Fitzrovia, London, England, owned by BT Group. It has also been known as the GPO Tower, the Post Office Tower,[3] and the Telecom Tower.[4] The main structure is 581 feet (177 m) high, with aerial rigging bringing the total height to 620 feet (189 m).[2]

Upon completion in 1964, it was the tallest structure in London and remained so until 1980. Butlins managed a revolving restaurant in the tower from 1966 until 1971.[5] A 360° LED screen displays news across central London.[6]

In February 2024, the sale of the tower to MCR Hotels, was announced.[7]

History

[edit]Design and construction

[edit]The tower was commissioned by the GPO. Its primary purpose was to support the microwave aerials then used to carry telecommunications traffic from London to the rest of the country, as part of the GPO microwave network.[8]

It replaced a shorter, 1940s steel lattice tower on the roof of the neighbouring Museum Telephone Exchange. The taller structure was required to protect the radio links' line of sight against tall buildings then planned in London. Links were routed via GPO microwave stations Harrow Weald, Bagshot, Kelvedon Hatch and Fairseat, and locations including the London Air Traffic Control Centre.[citation needed]

The tower was designed by the Ministry of Public Building and Works, under chief architects Eric Bedford and G R Yeats. Typical for its time, the building is concrete clad in glass. The narrow cylindrical shape was chosen as a stable platform for microwave aerials. It shifts no more than 25 centimetres (10 in) in wind speeds of up to 150 km/h (95 mph). To prevent overheating, the glass cladding had to be tinted.[citation needed]

Construction began in June 1961; owing to the building's height and its having a tower crane jib across the top virtually throughout the whole construction period, it gradually became a very prominent landmark that could be seen from almost anywhere in London. A question was raised in Parliament in August 1963 about the crane. Reginald Bennett MP asked the Minister of Public Buildings and Works, Geoffrey Rippon, how, when the crane on the top of the new Tower had fulfilled its purpose, he proposed to remove it. Rippon replied: "This is a matter for the contractors. The problem does not have to be solved for about a year but there appears to be no danger of the crane having to be left in situ."[9] Construction reached 475 ft by August 1963. The revolving restaurant was prefabricated by Ransomes & Rapier[10] and the lattice tower by Stewarts & Lloyds subsidiary Tubewrights.[11]

The tower was topped out on 15 July 1964, by Geoffrey Rippon[12] and inaugurated by Prime Minister Harold Wilson on 8 October 1965. The main contractor was Peter Lind & Company.[13]

The tower was originally designed to be just 111 metres (364 ft) high; its foundations are sunk down through 53 metres (174 ft) of London clay, and are formed of a concrete raft 27 metres (89 ft) square, 1 metre (3 ft) thick, reinforced with six layers of cables, on top of which sits a reinforced concrete pyramid.[14]

Initially, the first 16 floors were for technical equipment and power. Above that was a 35-metre (115 ft) section for the microwave aerials, then six floors of suites, a revolving restaurant, kitchens, technical equipment, and finally a cantilevered steel lattice tower. The construction cost was £2.5 million.[citation needed]

The first microwave link would be to Norwich on 1 January 1965. The Met Office put a weather radar on top of the tower.[15] Much of the telecommunications equipment was made by GEC.[16] The stainless steel clad windows were made by Henry Hope & Sons Ltd.[17]

Opening

[edit]

The tower was opened to the public on 19 May 1966, by Postmaster General, Anthony Wedgewood Benn and Billy Butlin,[18][19] with HM Queen Elizabeth II having visited on 17 May 1966.[20]

As well as communications equipment and office space, there were viewing galleries and a souvenir shop. Butlins' Top of the Tower revolving restaurant on the 34th floor made one revolution every 23 minutes[21][22] and meals cost about £4.[23]

In the first year there were nearly one million visitors,[24] and over 100,000 diners.[25]

Bombing

[edit]A bomb exploded in the ceiling of the men's toilets at the Top of the Tower restaurant at 04:30 on 31 October 1971,[24] the blast damaged buildings and cars up to 400 yards (370 m) away.[26] Responsibility for the bomb was claimed by members of the Angry Brigade, a far-left anarchist collective.[27] A call was also made by a person claiming to be the Kilburn Battalion of the IRA.[28]

The restaurant was closed to the general public following the 1971 bombing. In 1980, Butlins' restaurant lease expired.[29]

The tower has been used for events including a children's Christmas party and Children in Need 2010. It retains the revolving floor.[citation needed]

Recent

[edit]The tower's microwave aerials remained in use into the 21st century, connected to subterranean optical fibre links.[citation needed]

In 2009, a 360° coloured screen was installed 167 m (548 ft) up, over the 36 and 37th floors of the tower. It replaced an earlier light projection system and incorporated 529,750 LEDs arranged in 177 vertical strips around the tower. It was then the largest of its type in the world,[30] occupying an area of 280 m2 (3,000 sq ft) and with a circumference of 59 m (194 ft). It displayed a countdown of the number of days until the start of the 2012 Summer Olympics.[citation needed]

In April 2019, the screen broadcast a Windows 7 error message for almost a day.[31]

In October 2009, The Times reported that the revolving restaurant would be reopened in time for the 2012 London Olympics.[32] However, in December 2010, it was noted those plans had been "quietly dropped".[33]

For the tower's 50th anniversary, the 34th floor was opened for three days from 3 to 5 October 2015 to 2,400 winners of a lottery.[34]

The BT Tower was given Grade II listed building status in 2003.[35] Several of the defunct antennae attached to the building were protected by this listing, meaning they could not be removed unless the appropriate listed building consent was granted. Permission for their removal was given in 2011 on safety grounds, as they were in a bad state of repair and the fixings were no longer secure.[36] The last of the antennae was removed in December 2011, leaving the core of the tower visible.[37]

Entry to the building is by two high-speed lifts, which travel at a top speed of 1400 feet per minute (7 metres per second (15.7 mph)) and reach the top of the building in under 30 seconds. The original equipment was installed by the Express Lift Company, but it has since been replaced by elevators manufactured by ThyssenKrupp. Due to the confined space in the tower's core, removing the motors of the old lifts involved creating an access hole in the cast iron shaft wall, and then cutting the 3-ton winch machines into pieces and bringing them down in one of the functioning lifts.[38] In the 1960s an Act of Parliament was passed to vary fire regulations, allowing the building to be evacuated by using the lifts – unlike other buildings of the time.[39]

In 2006, the tower began to be used for short-term air-quality observations by the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology and this has continued in a more permanent form as BT Tower Observatory, an urban atmospheric pollution observatory to help monitor air quality in the capital.[40][41] The aim is to measure pollutant levels above ground level to determine their source. One area of investigation is the long-range transport of fine particles from outside the city.[42]

On 21 February 2024, BT Group announced the sale of BT Tower to MCR Hotels, who plan to retain the tower as a hotel.[7][43][44]

In popular culture

[edit]

The tower has appeared in novels, films and on television, including Smashing Time, The Bourne Ultimatum, Space Patrol, Doctor Who, V for Vendetta, 28 Days Later, 28 Weeks Later, The Union and Danger Mouse. It is toppled by a giant kitten in the The Goodies 1971 King Kong parody Kitten Kong.[45][46][47]

It was referenced by the Dudley Moore Trio's track GPO Tower used in the soundtrack for Bedazzled in which it also appeared.[48]

Two stamps depicting the tower, designed by Clive Abbott (born 1933), were issued in 1965.[49][50]

Races

[edit]The first documented race up the tower's stairs was on 18 April 1968, between University College London and Edinburgh University; it was won by an Edinburgh runner in 4 minutes, 46 seconds.[51]

In 1969, eight university teams competed. John Pearson from Victoria University of Manchester was fastest in 5 minutes, 6 seconds.[52]

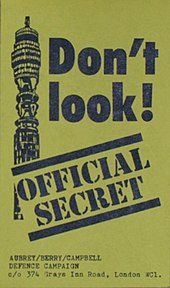

Secrecy

[edit]

Information about the tower was designated an official secret and in 1978, journalist Duncan Campbell was tried for collecting information about such locations. The judge ordered the tower could only be referred to as 'Location 23'.[53]

It is often said that the tower did not appear on Ordnance Survey maps, despite being a 177-metre (581 ft) tall structure in the middle of central London that had been open to the public.[54] However, this is incorrect; the 1971 1:25,000 and 1981 1:10,000 Ordnance Survey maps show the tower[55] as does the 1984 London A–Z street atlas.[56]

In February 1993, MP Kate Hoey used the tower as an example of trivia being kept secret, and joked that she hoped parliamentary privilege allowed her to confirm that the tower existed and to state its street address.[57]

Gallery

[edit]-

BT Tower under construction in the 1960s

-

View of the British Museum and the Thames from the BT Tower, 1966

-

BT Tower in 1970

-

BT Tower from Queen's Tower, 2007

-

Top of BT Tower from the London Eye

See also

[edit]- List of masts

- List of tallest buildings and structures in Great Britain

- List of towers

- List of tallest buildings and structures in London

- Telecommunications towers in the UK

References

[edit]- ^ a b "BT Tower". SkyscraperPage.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- ^ a b "We take an exclusive look behind the scenes at the BT Tower". BT. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Perkin, George, ed. (1968). Concrete in Architecture. London: The Cement and Concrete Association.

- ^ "BT Communication Tower". Historic England. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (27 March 2003). "BT Tower among icons of technology". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "BT Tower lights up with 'It's a Girl' in pink". ITV. 2 May 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ a b Kolirin, Lianne (21 February 2024). "The BT Tower, London's futuristic landmark, to become hotel". CNN. Archived from the original on 22 February 2024. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ Belfast Telegraph Thursday 2 February 1961, page 10

- ^ "Post Office Tower (Crane)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 2 August 1963. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Daily Herald Friday 1 November 1963, page 8

- ^ Birmingham Daily Post Wednesday 7 October 1964, page 7

- ^ Coventry Evening Telegraph Wednesday 15 July 1964, page 40

- ^ "BT Tower". lightstraw.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "BT Tower: serving the nation 24 hours a day", BT, 1993

- ^ Liverpool Echo Thursday 1 October 1964, page 8

- ^ Coventry Evening Telegraph Friday 8 October 1965, page 63

- ^ Birmingham Daily Post Monday 26 July 1965, page 24

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Post Office Tower Opening (1966)". YouTube. British Pathe. 13 April 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ "Post Office Tower – 18 May 1966, Volume 728". Hansard. Parliament. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Queen Enjoys View From The Top". British Pathe. 17 May 1966. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ "Look at Life - Eating high, 1966". YouTube. September 2011. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ Liverpool Daily Post Wednesday 3 June 1964, page 14

- ^ The Tatler Saturday 17 September 1966, page 51

- ^ a b "Events in telecommunications history". BT plc. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ Glancey, Jonathan (7 October 2005). "The great communicator". Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ "1971: Bomb explodes in Post Office tower". BBC News. 31 October 1971. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ "Bangor Daily News". news.google.com. Retrieved 21 April 2016 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ "BBC ON THIS DAY – 31 – 1971: Bomb explodes in Post Office tower". BBC News. 3 April 2007. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ^ "BT Tower to open for first time in 29 years". theregister.co.uk. 16 August 2010. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ "BT Tower of power: World's biggest LED screen set to light up the night". 31 October 2009. Archived from the original on 2 November 2009. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- ^ Thomson, Iain. "BT Tower broadcasts error message to the nation as Windows displays admin's shame". www.theregister.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Goodman, Matthew (1 November 2009). "High times as BT reopens its revolving restaurant". The Times. London. Retrieved 27 April 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "BT Tower Restaurant Won't Re-Open". Londonist. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Celebrating BT Tower's 50 ingenious years – come and visit the top of the BT Tower!". Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ "Honour for Post Office Tower". BBC News. 26 March 2003. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ "London's BT Tower to lose dish-shaped aerials". BBC News. 30 August 2011. Archived from the original on 28 April 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ "Engineers remove microwave dishes from the BT Tower in London". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "BT TOWER LIFT REMOVAL". Liftout - Corporate Site. Archived from the original on 22 February 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ "London Telecom Tower". Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Helfter, Dr Carole (28 June 2018). "BT Tower (London, UK): an urban atmospheric pollution observatory". UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "Research provides quality check on air pollution strategy". UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. 14 January 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "BT Tower in pollution study". Retrieved 8 November 2007.[dead link]

- ^ Laursen, Christian Moess. "BT Group Sells London's BT Tower for $347 Million to MCR Hotels". WSJ. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ Warren, Jess (21 February 2024). "BT Tower: 'Iconic' landmark to be turned into a hotel after £275m sale". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ "Golden opportunity to relive 60s and dine at top of BT Tower". The Guardian. 19 June 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ Jury, Louise (19 June 2015). "The BT Tower restaurant is going to reopen this summer!". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ "The Tower and the Glory: The BT Tower on Film (1960s parties and The Queen goes for a spin…) – British Pathé and the Reuters historical collection". www.britishpathe.com. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "Discogs - Bedazzled". Discogs. 1968. Archived from the original on 4 August 2024. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ West Lothian Courier Friday 6 August 1965, page 9

- ^ East Kent Times Wednesday 13 October 1965, page 11

- ^ "GPO Tower Race 1968: celebrating 50 years of UK tower running". Running UK. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ "GPO Tower Race To Top 1969". British Pathe. 23 January 1969. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ Grant, Thomas (2015). Jeremy Hutchinson's Case Histories. John Murray. p. 315.

- ^ "London Telecom Tower, formerly BT Tower and Post Office Tower, Fitzrovia, West End, London". urban75. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- ^ Kennett, Paul (August 2016). "Not so secret tower". Sheetlines (106). The Charles Close Society for the Study of Ordnance Survey Maps: 27. (The Charles Close Society)

- ^ A–Z London de luxe Atlas. Geographers' A–Z Map Company Ltd. 1984. p. 59.

- ^ "Column 634". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 19 February 1993. Archived 7 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- BT Tower (1964) at Structurae. Retrieved on 21 January 2015.

- British Telecom buildings and structures

- BT Group

- Butlins

- Communication towers in the United Kingdom

- Fitzrovia

- General Post Office

- Grade II listed buildings in the London Borough of Camden

- Observation towers in the United Kingdom

- Radio masts and towers in Europe

- Skyscraper office buildings in London

- Skyscrapers in the London Borough of Camden

- Towers completed in 1964

- Towers in London

- Towers with revolving restaurants

- Tourist attractions in the London Borough of Camden